Now it must be said that my perspective on worldbuilding comes from years of co-creationally telling stories around the table with my friends playing a game called Dungeons and Dragons.

Dungeons and Dragons is a collaborative storytelling game where one member of the group takes on the role of the narrator, or Dungeon Master, and everyone else plays the main characters, usually a group who are adventuring together. The game was originally built using theatre of the mind for its settings. The Dungeon Masters’ task was to narrate for the players what their characters perceived and what effects their actions had on their shared imaginary world. This makes worldbuilding absolutely critical as, in order for the players to feel like they can engage with the game, they must have enough information to be able to imagine themselves in it.

Take, for example, the following two scenarios. You are the Dungeon Master and the player’s characters walk into a tavern. There are three of them and they are looking for work to make some coin in the port city they have just arrived in.

DM:

“You walk into the tavern. You see lots of people and the barkeep. What would you like to do?”

Players:

“We talk to the barkeep and ask him for work.”

OR

DM:

“You walk into the bustling tavern. The smell of sweat mingles with the salt air from the docks outside and you can see weathered sailors and local fishermen gambling loudly at a few of the nearby tables. After he sees you enter, you notice that the barkeep, a grizzled old man, motions something to a boy sitting on a barrel near the back door. The boy quickly leaps down and exits at a run. What would you like to do?”

Players:

“I take a seat at the nearest table and start gambling!”

“I approach the barkeep and ask him why he sent the kid.”

“I ask the nearest sailor if they know of any captains looking for hired hands.”

Which gives you a better picture of the scene playing out before the characters? This added context irresistibly pulls you deeper into the story and immediately raises issues in your mind. Who was that kid and what possible motives could the barkeep have at sending him out after the characters arrived?

This is a classic example of worldbuilding.

It is the language we use to convey the landscape within which our characters, plot and central themes unfold. Everything from the descriptions of a home, to how we describe a figure sitting at a table, to the morals and laws of the cities or environments our characters find themselves in. All these things are part of the worldbuilding process.

And it works just the same for writers.

As writers, our characters are the ones playing out the main actions of our stories, but the importance of worldbuilding is still vital. Our characters, and by extension our readers, need to have enough information supporting them in order for the scenes playing out to be believable and engaging.

As a long-time Dungeon Master I can completely understand that for many writers the process of worldbuilding is one of trepidation and turmoil while for others it is a controlled playground for creative bliss. Whether you identify as the former or the latter, it is my sincerest hope that this article provides some inspiration for developing your own unique process and style when it comes to how you approach worldbuilding for your stories.

Let’s Start By Laying Some Foundation

How does worldbuilding serve us as writers? Why do we do it?

Worldbuilding gives our players, ahem readers the agency to feel grounded in the worlds in which our stories take place.

How we choose to incorporate that process into our stories can set us apart as writers, allowing us to present unique and thought-provoking settings for our readers to imagine themselves in and engage with. The result can add life and dimension to our settings while also providing important contextual support for our plot and characters to help them feel believable.

But there is a balance.

If our writing contains too many contextual descriptors, we can disrupt the pacing of the story and we run the risk of losing our readers in the details. If too little, we endanger our stories to being perceived as shallow and lacking in depth or relatability.

The process can also provide some great sources of inspiration while you are writing. As someone who frequently experiences stalls in my creative process, I’ve found it extremely helpful to be able to take a step back and imagine the world surrounding my characters in order to find inspiration for different paths that would further my central themes and plot. I often do this by asking myself a series of questions.

For example, what are some common things that would normally take place in a setting like this and could those be potential subplots? Could they add to how the main plot is unfolding? What are some things that wouldn’t happen?

At this point you may be saying, “This is all well and good Levi, but how do I use worldbuilding to make me the next insert preferred writing accolade or title here?”

Start Small

“But Levi, we are building worlds here! How can I possibly start small? Don’t my players hack readers have to be able to understand the entirety of my worlds’ nuanced history and diverse views and dynamics so that they can understand it, fall in love with it and then financially support me to expand on it!?”

Not exactly.

Please understand, there are a staggering number of guides, lectures and books available online aiming to teach successful worldbuilding and while some can be very useful, I often get bogged down by three things in particular.

First off, there seems to be no consensus in the writing community on what constitutes “good“ worldbuilding, which leaves it entirely on the author’s shoulders to decide how to best incorporate it into their writing.

Second, much of the instructional material prescribes a form of worldbuilding that exponentially expands in scope. A classic example of this would be advice along the lines of “Start by building out and describing the room your character is in, then the house the room is in, then the neighbourhood the house is in, then the city the neighbourhood is in..”

You get the idea. Don’t get me wrong, this can be a great way to build out a world but less useful on how to incorporate that world into your writing.

And lastly, I often find that the type of worldbuilding instruction given is genre specific, which is therefore only situationally helpful.

In my hopes of providing some constructive material for you, my goal is as follows:

To share how I begin my worldbuilding process after I’ve settled on a story I wish to tell. To provide some guidelines I follow as I begin to integrate that process into my writing. And finally, how I use that integration to reward my players cough readers.

How to Begin

When I sit down at my desk and keyboard, intent on committing a story I have in my head to writing, I begin by looking at the setting I’ve chosen for it and asking myself, “Why here?” Or in a more expanded form, “Why does the story I wish to tell take place in the setting that it does?”

This simple question does a fantastic job of providing a starting trajectory for your work because the answer will provide you with a few very important things.

- It tells you how integral your world is to the telling of your story. If you can take your entire story and have it completely change geographical locations without any rewrites, the amount of worldbuilding you will have to incorporate may be minimal. On the other hand, if the story you wish to tell involves imaginary races and dark lords and the existence of magic, you may have some substantial work ahead.

- It allows you to identify what information is important to your plot and what may be extraneous. This is critical because you only want to provide information that supports the central themes of your plot. If the context you are providing to a setting or scene is not pertinent to the current action, or a use of foreshadowing for later action to come, then cut it.

- It encourages you to start thinking differently about the settings you choose for the actions that happen throughout your story. Being able to describe why you chose the setting that you did as it relates to your plot will help you identify what to bring into your writing.

The Boundaries to Follow

There’s generally a lot here, so I’ll keep it to two of my favourites.

The world you’ve built is never more important than the plot.

This one rule covers a multitude of mistakes I often catch myself making while worldbuilding. Take the following instance, for example; you’re writing at your workstation, the creativity is flowing, and you storyboard a character or scene that sounds so fantastically cool that you instantly fall in love with it.

But it doesn’t quite fit into the story being told.

You wrestle with your outline, scanning the sections for some possible way to make them/it relevant to the plot but to no avail.

What do you do?

My advice?

Call a friend and tell them about it. And after, set that scene or character aside for a later story that they fit into.

Maybe the coolness would make up for the sudden change of pace or illogical shift in focus, but in my experience, the payoff is rarely there.

It takes a lot of discipline to put good writing aside and recognise that, while good, it isn’t pertinent to the story being told. Get into the heads of your characters. See the world you’ve built through their eyes and write through that lens. This can be a great way to gain perspective on what is actually important to a scene or instance of action in your writing.

I am a firm believer that not everything you write during the course of a novel is for that novel. I know this seems like redundant advice, but I’m constantly surprised when I can take out entire sections in my outlines and the plot remains perfectly untouched.

Keep it Concise

At least in my own writing, I can say with utmost certainty – less is almost always more. Yes, we as writers may be able to eloquently and gracefully weave entire chapters of in-depth descriptions and histories of every subject within our texts. BUT just because we can, doesn’t always mean we should. Absolutely there is a balance to this and trustworthy editors will help you find it, but my general rule of thumb is, if you can simplify things or combine characters to better focus your readers, do it.

How to Reward Your Readers

Offer payoff.

Take the principle of Chekhov‘s gun. Anton Chekhov was a famous nineteenth-century writer and playwright who wrote: “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.”

Write in a way that fulfils the players ack readers as they continue through your story.

Add seemingly unimportant details or character observations that come back in later chapters to be revealed as vital to the stories’ thoroughfare. Using unobtrusive inclusions of worldbuilding context for later payoff can be a great use of foreshadowing and also rewards your readers for paying attention. This can signal to the readers that the details you, as the writer, have chosen to include, regardless of emphasis, are integral to the narrative and can drastically change their engagement with it.

Final Thoughts

I’d like to end by saying – Have fun with it.

I know that worldbuilding as a process can seem incredibly daunting but if you start small, keep it focused and develop a process that best supports your unique writing and style, I think you‘ll find that it can be an incredibly useful tool to have in your adventurer’s backpack wheeze I mean writer’s kit!

This month’s guest blog was written by Levi Binder, a professional Dungeon Master and aspiring fantasy writer living in Vancouver.

If you want to hear more from Levi and to check out what he’s working on, follow him on Instagram @theardentnerd.

We at The Motley Writers Guild thank Levi for taking the time to write this detailed blog. We hope our readers will find it as helpful as we have!

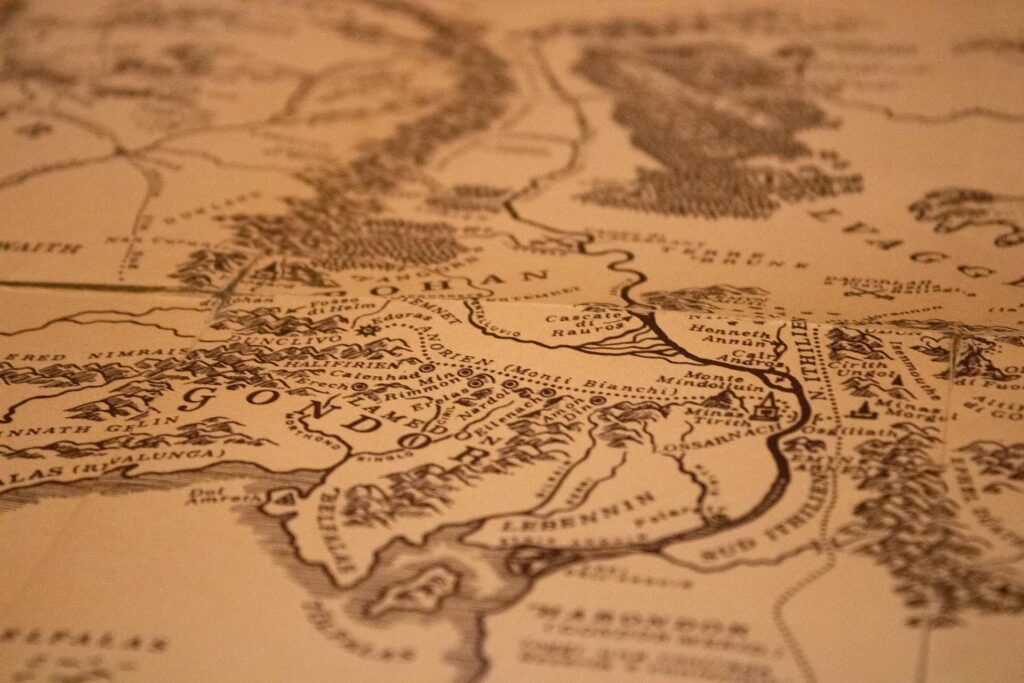

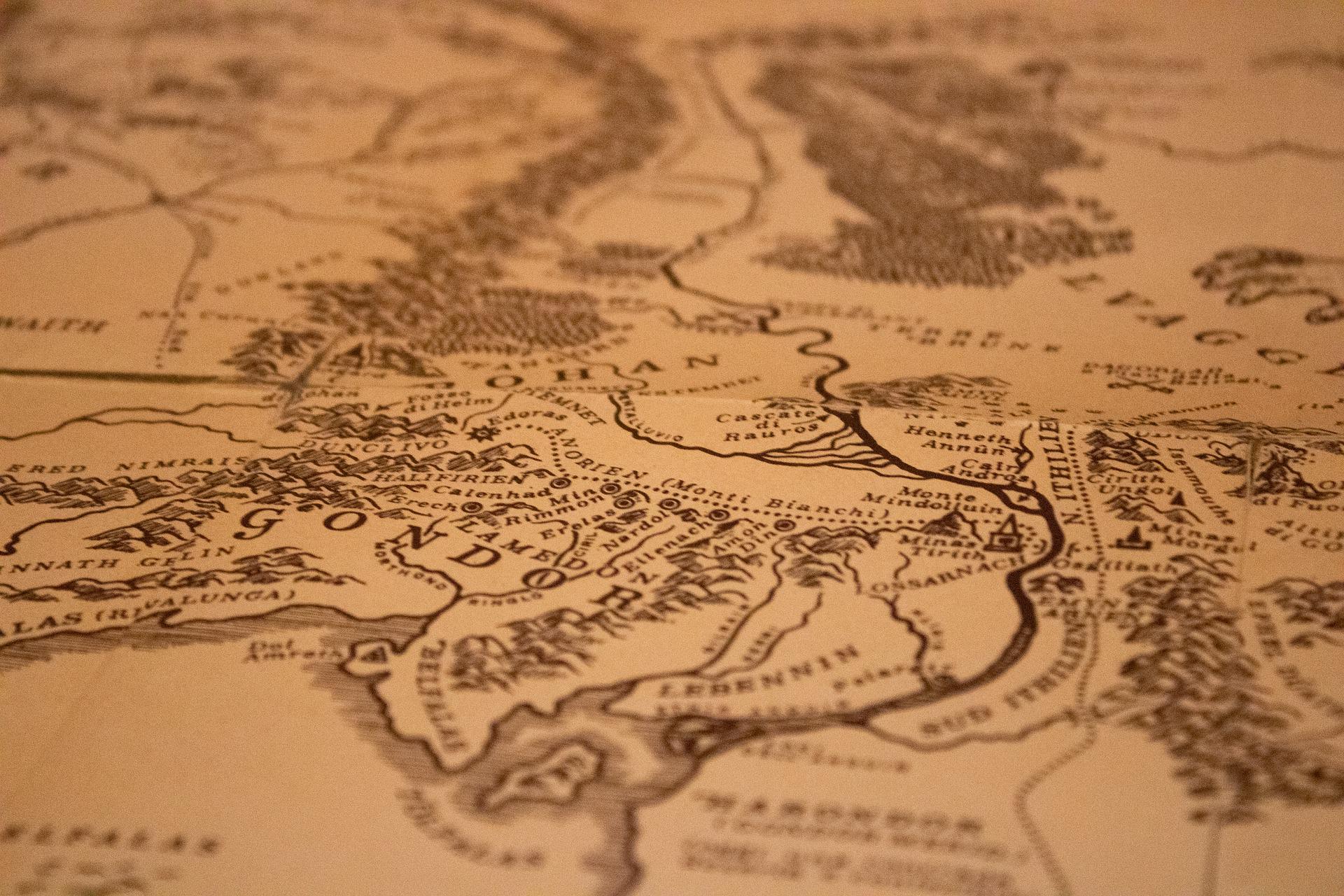

I loved it! It’s fascinating how much overlap there is between the two fields. I think my favourite takeaway is the idea of asking myself why my story is taking place in the setting it is. Often our characters will in some way help shape their world, but it’s important to remember that the world shapes our characters too. Frodo could only have come from the shire.